The new AI Act must build consumer trust and safety to unlock innovation

Progress has been slow since April 2021 when the draft proposal for an AI regulation was first published. However, now that the joint parliamentary committees have been named, we can expect things to speed up. While it is not entirely clear yet how the Civil Liberties (LIBE) and the Internal Market (IMCO) committees will divide the work, the Parliament will soon begin working in earnest on the regulation. With the upcoming French Presidency focusing on innovation and digital files, we could optimistically expect a first Parliament position before the 2022 summer break.

But it will not be an easy process. The regulation is the first of its kind in the world, and is dealing with a technology which, according to the AI Act’s introduction has the potential to “adversely affect a number of fundamental rights enshrined in the EU Charter”. The technology is also relatively new in terms of being applied in real life settings, and there is little agreement so far on the best way to minimise these risks.

In addition, the regulatory approach chosen is complex and blends different approaches in somewhat novel ways, taking a product safety approach which involves harmonized technical standards developed by private standardization bodies – something that some fear will lack democratic oversight.

AI technology is also complex, involving a lot of stakeholders with greatly diverging perspectives on what AI is, its innovative potential, how it can be controlled and where it should be applied. Consumers are among the many stakeholders impacted by AI and, while they may not have technical expertise they have clear feelings about it.

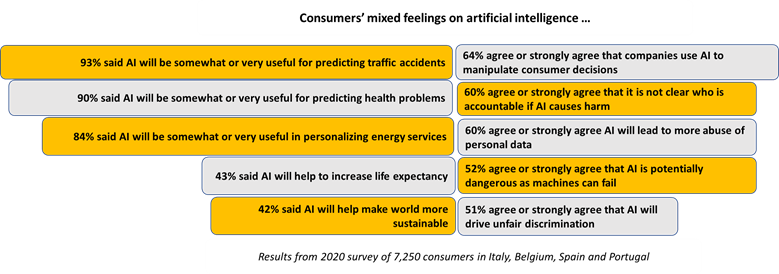

Consumers are optimistic but also concerned about AI

A major Euroconsumers’ survey in 2020 found that consumers think services have the potential to be really helpful and were particularly optimistic that AI technology could help speed up the sustainability transition. On the other hand, a significant share of consumers fear that AI can and will lead to exploitation and abuses of privacy.

In a more recent survey about AI applications in smart cities, consumers overall find AI useful to improve life in the city, whether it be for controlling city lighting more efficiently (86%), optimising public transport (85%) and waste collection (84%) and managing city traffic (84%). But again, faith in governments and companies to manage AI for the benefit of everyone was low, very few consumers believe current legislation is adequate to efficiently regulate AI-based activities (14%), or even trust national authorities to exert effective control over AI organizations and companies (18%). Therefore, while consumers are very welcoming of the idea of AI but to build trust in AI, a strong regulatory framework needs to be created and implemented.

How the AI Act can build more consumer trust

If consumers feel that companies developing AI services and products are not accountable or don’t have their best interests at heart, they will be reluctant to use it which means the positive benefits of AI won’t be achieved. Successful, beneficial AI needs the support, engagement and trust of consumers – so what needs to change in the AI Act proposal to build this consumer trust?

- Cover all consumer AI products and services: the current draft bans a selection of uses (such as social scoring) and regulates a narrow selection of AI systems described as posing potentially ‘high-risk’ for fundamental rights such as those used for recruitment or justice systems. However, it leaves out major areas like consumer finance where AI is used to decide insurance premiums. Plenty of other AI-powered services that carry risks are excluded too such as virtual assistants, toys, social media and recommender systems. All of these carry some level of risk – if they all respected a set of common principles like transparency, fairness and non-discrimination then consumers could have more trust in them.

- Respect consumer autonomy and don’t manipulate: there are some strict rules proposed around manipulation but they are somewhat limited. “Subliminal manipulation resulting in physical or psychological harm” is banned outright, as is the “exploitation of children or mentally disabled persons resulting in physical/psychological harm”. In both these cases, the type of manipulation, the category of consumer and the nature of the harm is tightly defined. This leaves out a whole range of other types of manipulation. For example, under these rules, an AI system that exploits a problem gambler to carry on betting and suffer financial harm would be allowed. It also assumes that only a very narrow category of consumers are vulnerable, when in fact, anyone of us can find ourselves in vulnerable circumstances at different times. Consumer trust could be built by creating much firmer definitions of the context and situations where people may be vulnerable to AI systems.

- Understand a full range of potential harms: AI is a complex technology with the potential power to bring a huge range of benefits, but also a wide reach of harms. This should not stop development but it does require taking a holistic look at what could go wrong in order to ensure consumers and society are safe. The current draft AI Act refers to harms but doesn’t give a full definition. We’d like to see a much clearer concept of how harm is understood in the Act that lines up with other EU safety approaches, covering damage to health, property, the environment, security, economic harm to consumers and collective harms to society. Demonstrating that the full breadth of potential harms have been given as much thought as the potential benefits will show consumers that the unknown risks of AI are being taken seriously.

- Open and accountable providers: the proposed AI Act relies exclusively on self-assessments of conformity by the AI operators. We believe that for some risky AI applications, there should be ex ante oversight by a public authority. There must also be clear pathways for consumers to report harmful systems and get redress for damages. This will send a clear message that providers will be held to account for any harm they cause.

- Treat consumers fairly and don’t discriminate: Given that public authorities have been among the first customers of AI systems, we have become familiar with examples of discrimination in areas like sentencing or health care allocation. However, the potential for discrimination against people on the basis of their profile and behaviour is alive in consumer settings and can cause economic harm as well as impacting on fundamental rights. In the proposal, social scoring is banned for use by public authorities but not for commercial purposes, which means that a company could use an AI system to socially score a potential customer and either exclude them or offer them a different price. All potentially discriminatory uses that cause harm should be included in the regulation, regardless of whether they are designed for public or commercial consumer uses.

Trust and innovation go hand in hand

Innovation will be much easier to deliver if there is consumer trust, this relies on demonstrating that the potential risks of AI have been given as much weight as the potential benefits and that consumer concerns about losing privacy and control, being manipulated and not being able to get redress are openly addressed.

The AI Act contains plenty of measures to foster innovation, such as the regulatory AI sandboxes which could potentially nurture many innovative new applications. We believe that this is a valuable tool that can shape the environment in which companies and researchers can create AI that meets the trust requirements of consumers and is safe, beneficial and respectful of privacy.

In the spirit of co-creation and trust building, we want to explore how consumers and consumer organisations can play a role in providing valuable input for AI researchers and developers, of course under the right safeguards and conditions. We also welcome the measures that will lower the threshold for small-scale providers and users to interact with the field of AI. As the proposed regulation progresses, Euroconsumers and its members will be campaigning, with BEUC, to ensure that consumer interests are central to the regulation, delivering to them the innovation consumers are calling for and is fostered by openness and trust.

trust.