Digital Markets Act: will the DMA rebalance online markets?

Passed in July 2022 and published today in the EU Official Journal, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and its sister legislation the Digital Services Act (DSA) mark a significant milestone in EU digital regulation.

Both Acts work in tandem on the overall objective of loosening the grip that the very big digital companies have on service provision – either in their role as powerful intermediaries and platforms or their holding of vast swathes of consumer data.

The DMA focuses on competition, and the market share (and data share) of large tech players, while the DSA replaces outdated e-commerce rules from over 20 years ago with much stricter intermediary responsibilities for platforms dealing with harmful content, goods and services.

This blog takes a closer look at the content of the DMA and considers how other jurisdictions are approaching similar issues.

DMA demands more from digital gatekeepers

At the core of the DMA is a definition of very large online platforms who are considered to be ‘gatekeepers’ able to abuse their market position to the detriment of other, smaller companies.

Gatekeepers, like Google and Meta, are an entrenched and vital part of the consumer experience and digital market infrastructure. However, their ability to buy up competitors, dictate the behaviour of suppliers and partners who rely on their services to function and their massive data holdings put them in a position of unfathomable power.

With this kind of power comes special responsibility. In short, the DMA wants to rebalance the digital marketplace in order to safeguard that smaller players’ ability to compete with these larger multinationals.

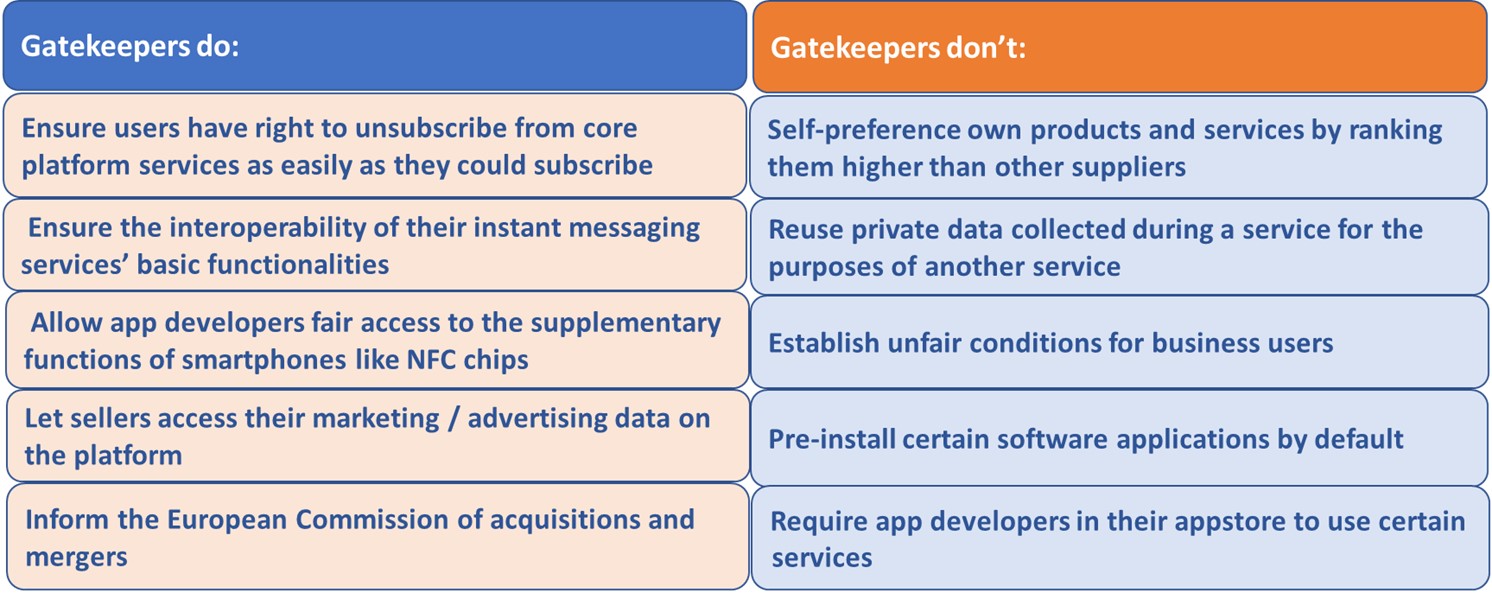

DMA lists do’s and don’ts for gatekeepers

A gatekeeper is defined by a combination of its annual turnover (at least €7.5 billion EU or market valuation of at least €75 billion); number of EU end users (45 million consumers per month and at least 10,000 business users); amount of control over a core platform including marketplaces and app stores, search engines, social networking, cloud services, advertising services, voice assistants and web browsers).

DMA includes tough sanctions

As ever, the enforcement procedures will be critical to the success of this ambitious legislation. Consumer groups have welcomed the strong sanctions and procedures such as fines of up to 10% of its total worldwide turnover for a first-time violation of rules, and up to 20% for repeat offences.

These rates are much higher than those in the GDPR and some have objected to having the European Commission as sole enforcer of the regulation instead of national regulators. But this arrangement addresses some other GDPR enforcement challenges such as under-resourced small nation data protection authorities dealing with huge complaints against well-resourced companies.

Anti-trust legislation around the world

USA

The Biden administration was not enamoured of the DMA, given that its definition of gatekeepers was likely to only cover US companies and that fines were based on global turnover and not on revenues within Europe. However, two anti-trust bills are slowly progressing through Congress addressing similar practices with similar provisions.

The American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICO), addresses the conduct of large, dominant platforms such as self-preferencing that disadvantages competitors. The Open App Markets Act (OAMA) calls for large app stores to loosen restrictions on app developers – an area already subject to private and public enforcement across the world.

The Acts use the term ‘covered companies’ or ‘covered platforms’ which, like the EU’s gatekeeper definition, takes the number of users of an entity as a key element to define their status. A key difference between the two jurisdictions is that the US Acts propose allowing justifications for their behaviour (for example, resisting a change based on security or privacy grounds) whereas the DMA leaves very little wriggle room for prohibited practices.

UK

In the UK, a Draft Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill was recently announced which will create new competition rules for digital markets and the largest digital firms. Tackling similar issues to the DMA, AICO and OAMA, the bill’s goal is to ensure that “businesses across the economy that rely on very powerful tech firms […] are treated fairly and can succeed without having to comply with unfair terms.”

Instead of ‘gatekeepers’, the UK refers to the targets of regulation as those with ‘Strategic Market Status’. This refers to firms with substantial and entrenched market power in at least one digital activity which gives them a widespread and significant strategic position.

Firms with Strategic Market Status will be subject to individualised, enforceable code of conduct setting out expected behaviours on fair trading, open choices and trust and transparency, shaping firms’ behaviour to prevent bad outcomes before they occur. Mandatory notice of mergers and acquisitions will also be required. The digital competition rules will be overseen by a new stand-alone tech regulator for the UK called the Digital Markets Unit. This unit is already carrying out investigations that align with European Commission priorities such as mobile ecosystems, online advertising and content streaming services.

Impact of DMA depends on strong enforcement

The DMA’s new digital rules will significantly impact the way digital markets work. Not surprisingly expectations for the new DMA are high, ensuring fairer and more competitive digital markets, boosting innovation, and delivering greater choice and protection to consumers. And, if platforms face similar pressures in other major markets as looks likely in USA and UK then the prospect of major changes increases.

However, as always, the proof of the pudding will be in effective enforcement. The European Union’s strong reputation for digital policy leadership is not matched by its enforcement. Public and private means of enforcement are limited, and the legal and financial resources of global digital players far outweigh that of public authorities.

It is vital that the Commission is equipped with the necessary in-house expertise and enforcement resources so that they are able to step in the moment there is foul play.